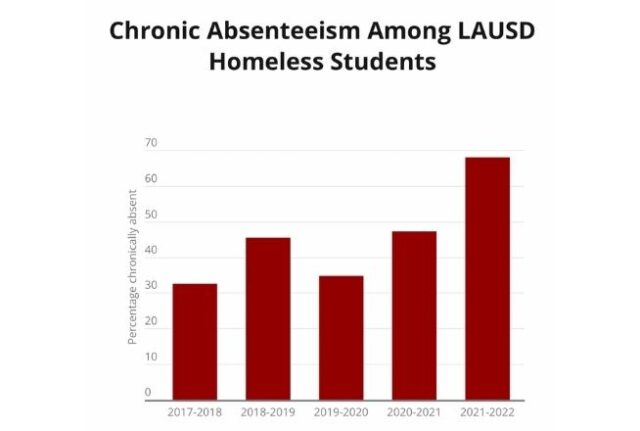

Nearly 70% of homeless students in Los Angeles Unified chronically absent last year

Rebecca Katz | July 19, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Jennifer Kottke has worked with LAUSD homeless and foster care youth for more than 20 years — but she has never seen chronic absenteeism among these students become the crisis it did during the pandemic.

While nearly half of all LAUSD students were chronically absent during most of the the 2021-22 school year, the numbers among homeless and foster care youth are staggering: Nearly 70% of homeless LAUSD students, and nearly 60% of students in foster care were chronically absent during the last school year, according to school system data.

The statistics, provided by LAUSD, covered September 2021 to mid-March of 2022. The two groups made up the highest percentage of chronically absent students.

“The numbers are alarming,” said Jennifer Kottke, coordinator of homeless education at the Los Angeles County Office of Education. “These families are already struggling with basic stability … Now they have to contend with all kinds of pandemic-related problems.”

Since the pandemic began, homeless students have faced increased challenges making it harder for them to attend school — both remote and in person — regularly. Many are not new issues for these students but were exacerbated by the pandemic, advocates said. They include lack of internet access and moving more often as parents took on new or additional jobs. In some cases homeless students had to get jobs themselves; or they had to stay home to take care of siblings while parents worked.

Whatever the reasons, the pandemic created a perfect storm leading to the majority of LAUSD homeless and foster care students missing out on many classes during the last school year.

Just five years ago, during the 2017-18 school year, the percentage of chronically absent homeless youth stood at 32.6%. In the 2021-22 school year, it was 67.9%, more than 35,000 students.

Chronic absenteeism among foster youth also rose dramatically since the pandemic. In 2017-18, foster youth chronic absenteeism was at 34%, while last academic year it stood at 57.7%, nearly 4,000 students.

Chronic absenteeism, defined as a student missing at least 9% of days in the school year, has increased for students nationwide since the pandemic began in 2020. The chronic absenteeism rate for all LAUSD students in the 2017-18 school year was 15.6%.

In Los Angeles, homeless youth and foster care advocates were not surprised at the massive increases among the vulnerable students.

“Unfortunately the numbers are not surprising to me,” said California Homeless Youth project director Pixie Pearl. “If basic needs aren’t being met then we can’t expect kids to get to school.”

Pearl said she sees unhoused students struggling with everything from lack of access to nutritional foods to mental healthcare, all things that could make it difficult to consistently get to school and all things that became harder to access during the pandemic.

There are more than 51,000 homeless students in Los Angeles public schools; and just over 7,000 students currently in foster care. This definition of homeless includes any student living on the streets, in a tent, motel, or sleeping on friends’ and relatives’ couches because of economic instability.

Right from the start of the pandemic, homeless students were at a disadvantage, advocates said.

“During the beginning of the pandemic, students needed regular wifi access to engage in school and be counted as present … Most homeless students often didn’t have either consistent internet access or a stable quiet place to do online school, so the data is going to show that,” said Marian Chiara, coordinator for California’s attendance review board.

When school went remote, Kottke said that many homeless students started working to help support their families. Some students got work permits and began working in fast-food restaurants. Some helped or took over their parents’ jobs – gardening or nannying or looking after their siblings while their parents worked longer hours to make ends meet. When school returned to in-person learning, students continued prioritizing work, leading to more missed school days.

“Some students got jobs and just never went back to school,” Kottke said.

Unhoused and foster youth are also dealing with a lot of emotional trauma that only heightened during the pandemic, possibly keeping them from attending classes, said Kottke. “These are students that are already dealing with so much instability and the pandemic added a new layer of uncertainty and emotional turmoil.”

Naomi Ondrasek, a researcher on homelessness at the Learning Policy Institute, also pointed out that during the pandemic, these vulnerable students were switching schools more often because their parents were having to move for work which made them have to confront more emotional challenges such as making new friends and establishing connections with new teachers.

“If students feel disengaged from their new school, that can definitely lead to more absenteeism,” Ondrasek said. “The emotional issues brought on by the pandemic, especially for these vulnerable groups, have been huge … these students need more support than most schools can offer them.”

Kottke emphasized the need for more mental health professionals that can support vulnerable student groups to make sure they feel emotionally stable and well enough to come to school. Since the pandemic, school board members have agreed that hiring more mental health professionals is a priority for the district, but last fall KCRW reported that only 25% of the 922 new psychiatric roles had been filled.

“We need so much more support for these kids,” Kottke said. “With vulnerable students who are chronically absent, we need people to help figure out what’s going on emotionally. Where did the relationship break with the school and how can we best repair that to make them feel comfortable again?”

The way the district deals with chronic absenteeism has shifted a lot in the last decade. Chiara said that previously when students were chronically absent they went to the attendance review board and it was really a “punitive measure.”

“Now, the attendance review board is a restorative practice … we want to understand why students aren’t getting to school regularly,” Chiara said.

LAUSD schools now try to combat absenteeism by having one-on-one meetings with the parents, regular check-ins, and assigning a therapist to the family, Chiara said. “It’s really about having the attendance board help get the student and family the services they need to feel supported in all aspects of their lives.”

LA Unified has tried to further curb chronic absenteeism by partnering with more outside groups that help students get the basic resources they need to “foster a sense of stability” in their lives.

“In alignment with the Superintendent’s plan, the Homeless Education Office addresses the mental health and wellness of our school communities by leveraging existing external partnerships to increase access to basic needs for students and families,” said a Los Angeles Unified spokesperson.

Pearl said the L.A. school system can still do much more for students experiencing homelessness. She said that schools hosting community fairs where there is one place to go for things like hygiene products, food stamps, signing up for mental health and medical services, and housing would be helpful. Pearl said that in some Sacramento public schools, community fairs have become regular occurrences.

“We shouldn’t wait for this big deficit to be providing to our students,” Pearl said. “Community fairs should be a consistent thing so students know they can find support and resources at their schools.”