Kids catch up best with grade-level work — but keep getting easier assignments

Beth Hawkins | August 24, 2022

Your donation will help us produce journalism like this. Please give today.

Mounting evidence supports an academic strategy known as acceleration, in which students who are behind are challenged with grade-level material while getting help with missing skills or knowledge. But new research finds its use in schools “is currently more talk than action.”

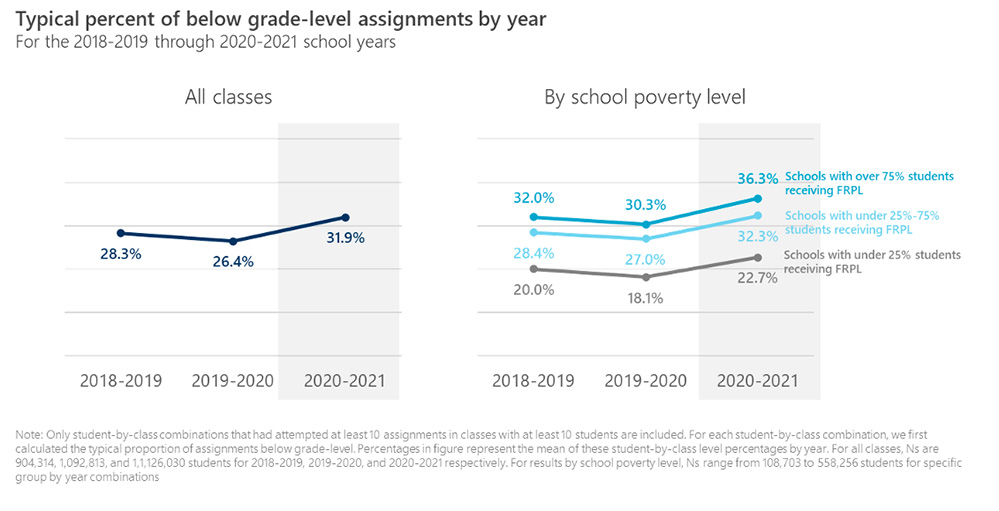

Analyzing data from 3 million students assigned lessons through a widely used literacy program, the nonprofits ReadWorks and TNTP found that during the 2020-21 school year — the first full year after the start of the pandemic — students were assigned work below their grade level a third of the time. Children in high-poverty schools were given less challenging materials more often than their affluent peers — even when they had already mastered grade-level assignments.

“Our analysis reveals a stark disconnect between the extent of students’ unfinished learning during the pandemic and the opportunities they’re getting to engage with the grade-level work they need to catch up,” states a report outlining their findings. “It suggests that while many school systems are talking about learning acceleration, far fewer have implemented a successful learning acceleration strategy.”

Formerly known as The New Teacher Project, TNTP focuses on improving instruction. ReadWorks provides free digital literacy materials.

The report adds to a body of research that predates COVID. In 2018, TNTP found that overall, students spend some 500 hours a year — the equivalent of six months — doing work below their grade level. Teachers are often trained to provide materials that align with what they perceive to be students’ level of mastery in the hope that success will bolster their confidence.

But in practice, instead of giving students a firmer academic footing, assigning earlier-grade material holds them back, the group reported. More worrisome, what is often referred to as remediation is not very effective at catching kids up and has a compounding effect as years go by with no exposure to challenging work.

The report comes on the heels of similar findings by Zearn Math, which recently released data covering 600,000 students in the first two years of pandemic-era schooling. Students taught with acceleration strategies completed twice as many grade-level lessons and struggled 17% less than when they were remediated, Zearn’s team found. Black, Latino and low-income students were more likely to be remediated in math — even when they had already mastered grade-level work.

Last year, TNTP released research showing that acceleration using grade-level material is the best way to help students catch up in math — a case also made by Zearn and the assessment concern NWEA. The authors of the new report, which may be the first about acceleration in English language arts, say they hope the ReadWorks data will embolden teachers to assign work they anticipate students will struggle with.

“The issue with not reading at grade level is that students get behind,” says Susanne Nobles, ReadWorks’ chief academic officer. “They’re not exposed to [grade-level] vocabulary and sentence structure.”

Now, she says, “we have this data to show it’ll be okay if you give students this grade-level material.”

The analysis examined 75,000 schools serving 12 million children in all grades, focusing on students in classes of at least 10 who attempted ReadWorks assignments 10 times or more in the 2018-19 through 2020-21 school years.

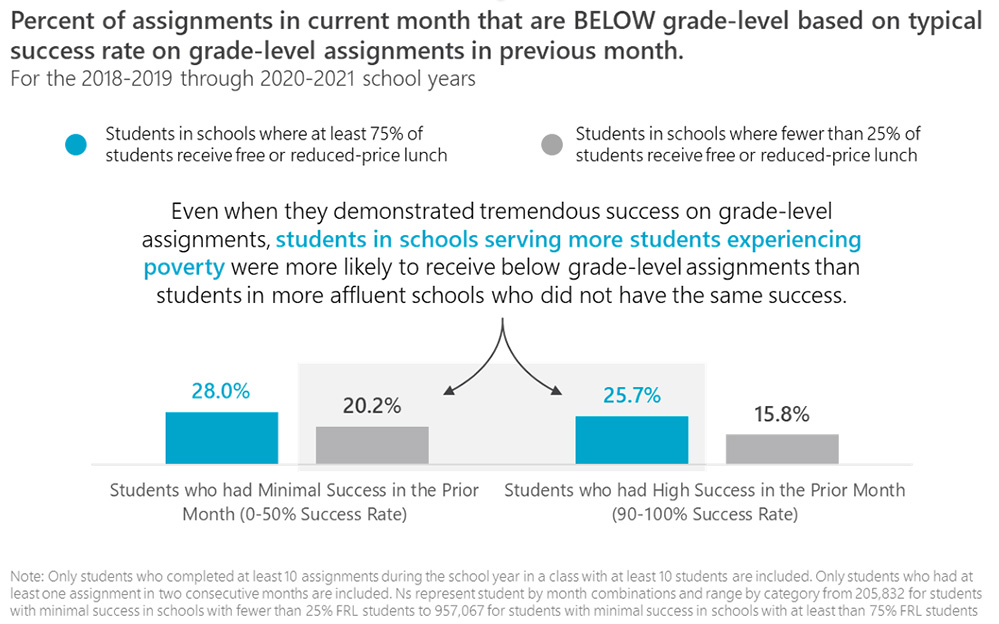

The new report found that far from adopting acceleration, teachers gave students 5 percentage points more below-grade-level material than before the start of the pandemic. Children in high-poverty schools spent about 36% of their time on less challenging materials, compared with 23% in the most affluent schools. About a quarter of students, predominantly low-income children of color, were given below-grade-level work for the entire school year.

“In those schools, when students correctly answered more than 90% of the questions on their previous month’s grade-level assignments, almost 25% of their assignments were still below grade level the next month,” the report notes. “In fact, these students received less grade-level work than students in more affluent schools who consistently struggled with grade-level assignments. There seems to be nothing many students in high-poverty schools can do to break free of negative assumptions about their abilities and ‘earn’ access to the grade-level work they need to be successful.”

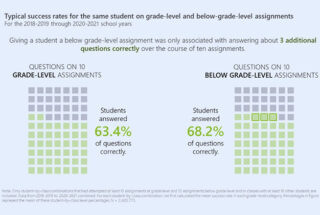

Indeed, pupils in ReadWorks’ sample were just as successful on grade-level work as they were on remedial content, answering nearly two-thirds of questions correctly regardless of the difficulty of the assignment.

“This builds on our findings in our past research that assigning students work below their grade level mainly just denies them important opportunities to engage with material they could master if given the chance,” the researchers state.

The report contains one important caveat. Students missing the foundational reading skills to understand phonics and turn printed words into sounds will need different learning acceleration that prioritizes those elements.

TNTP also has produced an acceleration “toolkit” with advice for teachers on putting the strategy into practice and for school system leaders hoping to make sure their COVID recovery efforts and relief funds support it.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to TNTP, ReadWorks, Zearn and LA School Report’s parent company, The 74. The Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to TNTP and LA School Report’s parent company, The 74.

This article was published in partnership with The 74. Sign up for The 74’s newsletter here.